A few centuries ago, the word fatigue did not exist. The words boredom or lassitude, then neurasthenia were used. In the medical press, the first descriptions of patients with symptoms of lack of energy and weakness appeared at the end of the 19th century [1]. Fatigue was then called the ‘disease of modern civilization’. Of course, when reading George Vigarello’s ‘History of Fatigue’ (in French) [2], one finds long before that descriptions of fatigued or even exhausted human beings. But for obvious reasons. This is the case of the farmers in the Alps, at the end of the 18th century, acknowledging that they “did not live long” because of the “frequent fatigue of going up and down the mountain“. It is also the case of the galley slaves “rowing 10, 12 and even 20 hours in a row without the slightest break” with as only pittance “a piece of bread soaked in wine to prevent them from failing“. But the fatigue that we are going to talk about in this blog article does not have, most of the time, an easily identifiable cause.

Simpler in English

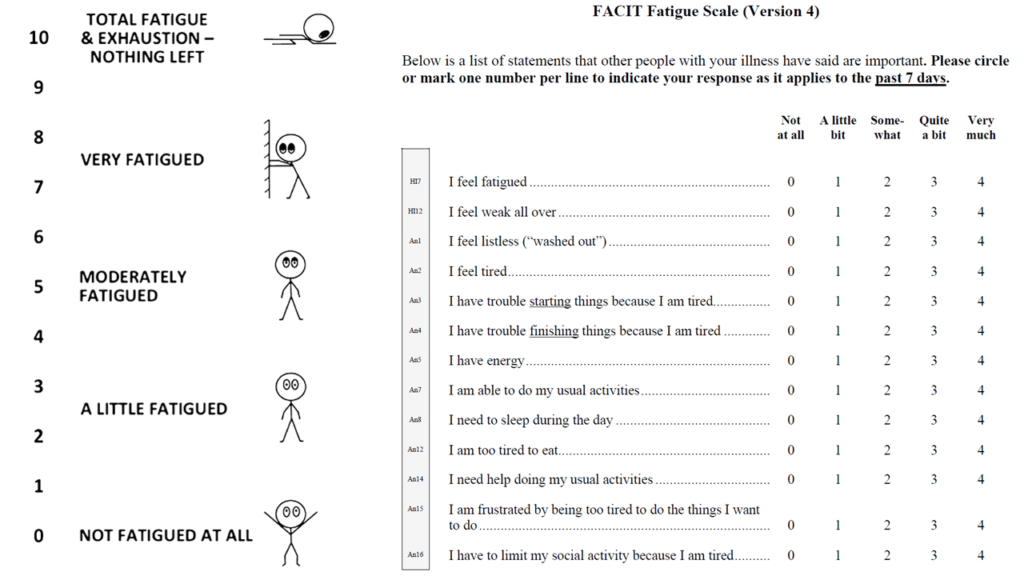

In French, the same word ‘fatigue’ is used to describe two very different phenomena. The first meaning is that of a symptom of physical and/or mental weakness from which one does not recover despite rest and sleep. For example, fatigue in cancer patients is defined as “an unusual and persistent feeling of fatigue related to the disease or cancer treatments that interferes with the person’s usual functioning” [3]. It is therefore a chronic fatigue, usually measured with subjective self-report tools, i.e. questionnaires such as the Facit-F or fatigue scales such as the ROF (see figure below).

In total, there are no less than 40 scales or questionnaires to assess fatigue [4]. The second meaning of the term ‘fatigue’ in French refers to what happens after physical or mental exercise. In English, it is a little simpler because two different terms are used nowadays, ‘fatigue’ being associated with chronic fatigue and ‘fatigability’ with acute fatigue. When doing fatiguing physical exercise, whether it is going to the grocery store for a disabled person or running an ultramarathon for a very fit person, it is possible to objectively measure what is happening. By measuring maximal voluntary contractions (maximal strength) and evoked stimulations (electrical or magnetic stimulation of the muscle or nerves), one can observe a decrease in functional capacities: the person is less strong or less powerful after the exercise than before and the more strength is lost, the greater the fatigue. Simple! Fatigability can nevertheless be divided into ‘performance fatigability’ (also called neuromuscular fatigue) and ‘perceived fatigability’ measured subjectively by a scale often graduated from 0 to 10 (how the person feels during exercise): either the ROF, or the classic Borg scale. What is the difference between the ROF and the Borg effort perception scales? In theory, the latter cannot be used if no effort is made. Fatigue does not disappear immediately as soon as you stop exercise but effort does [1].

Multiple deleterious consequences

As mentioned above, in this article I will mainly talk about chronic fatigue. Not a trivial affair. To begin with, it reduces the ability to carry out activities of daily life and even delays the return to work. For example, five years after treatment for Hodgkin’s lymphoma, 51% and 63% of women and men with severe fatigue were working or in vocational training, respectively, compared to 78% and 90% of those without severe fatigue [5]. In addition, fatigue in adults with osteoarthritis was reported by patients to be more of a problem than pain, and it was fatigue rather than pain that limited physical activity [6]. Here, we are not talking about running a marathon, but simply being active enough to go shopping or do housework. Considering these data, it is easy to guess the effects that fatigue can have on quality of life and health, which, as a reminder, is defined by the WHO as the state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. Fatigue is even an independent predictor of mortality in the elderly and in cancer patients [7-10]. In other words, it reduces life expectancy. And if you are not sensitive to quality of life and health, let’s try the financial argument: fatigue also has a significant cost to society. Not only does it impair work performance and induce increased absenteeism, but it also leads to increased health care utilization [11]. In short, there is an urgent need to address this issue.

Non-fatigued people, a step forward

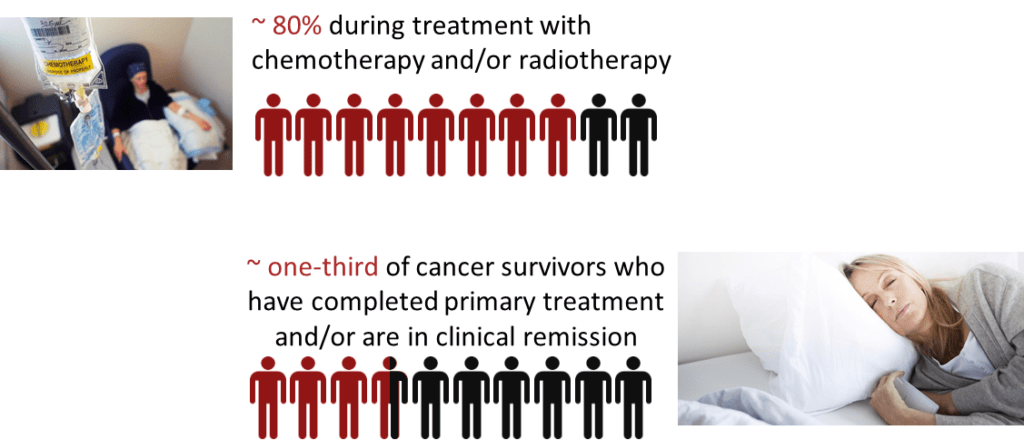

Chronic fatigue is the main complaint of patients in many diseases, including cancer [12, 13], multiple sclerosis [14], intensive care unit stays [15], chronic venous disease, elderly people with osteoarthritis [6], etc. And, of course, two diseases characterized by a high level of fatigue: chronic fatigue syndrome (also called myalgic encephalomyelitis) and fibromyalgia. Plus long Covid. It is so prevalent that it would be quicker to list the diseases where the majority of patients are not fatigued. If we zoom in on cancer, one of the diseases where fatigue is the most problematic, we see that it a reality in all types of cancer, at all stages of the disease and whatever the type, extent and duration of treatment [16]. Fatigue is often the symptom that appears first and disappears last, and most people undergoing cancer treatment will experience fatigue (e.g. ~85% during chemotherapy). Even more problematic, about one in three or four people experience fatigue for months or even years after treatment ends.

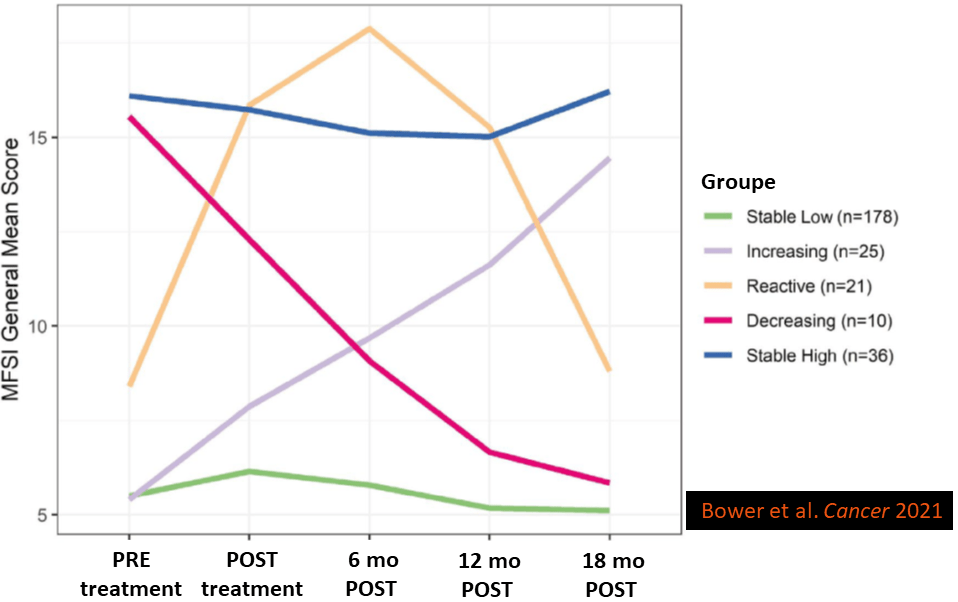

In some cancers, such as myelodysplastic syndromes, fatigue can be as high as 90% and can last for years [13]. Outside of cancer, it has been shown that more than one out of two people remain clinically fatigued after being admitted in intensive care units (ICU). Again, this can continue for several years after discharge [15]. ICUs are quite “popular” since the arrival of Covid-19, but contrary to what one might think, it seems (let’s be careful, this observation must be confirmed) that the level of fatigue, a major symptom of Long Covid, does not depend on the severity of Covid-19. For example, a patient we wanted to include in one of our fatigue studies did not answer the phone because he was… chopping wood with his son, less than 2 months after ICU discharge. On the other hand, some people who contracted Sars-Cov-2 and who were not even hospitalized, were knocked out for months.. For a given disease, fatigue also depends on the treatment (for example, it is more likely go be fatigued after chemotherapy than after radiotherapy) and its duration. The risk of remaining fatigued also increases when one has a history of depression or sleep disorders, which may be related. But these are all statistics. The truth is that it’s hard to tell who will stay fatigued and who will recover. For example, one study showed that the trajectories of fatigue between diagnosis and 18 months post-treatment after breast cancer were very heterogeneous (Figure below) [12]. Note that the treatments were relatively short in this study, which explains the lower fatigue levels than the figures we provided above for cancer.

As the number of survivors (of cancer and other diseases) increases due to advances in treatment [17], the number of people suffering from fatigue also increases. Paradoxically, more people suffering from fatigue is a good thing, but it also makes research on fatigue and, more importantly, on effective ways to combat it, increasingly relevant. This being said the prevalence of fatigue among people in remission seems to have decreased over the last 25 years, perhaps due to the publication of guidelines [3] and to the progress in treatments, which are less ‘aggressive’ than they used to be. Nevertheless, with the increasing number of survivors and all the consequences of fatigue we mentioned above, fatigue should figure as an essential scientific and medical field. Unfortunately, this is not the case! Fatigue is not always taken seriously. For instance, 94% of oncologists treat pain but only 5% treat the fatigue of their patients [3]. It is as though fatigue were unavoidable so we just have to live with it. We cannot really blame the doctors: if fatigue is insufficiently treated by health professionals, this is mainly due to a lack of knowledge of its causes and of what must be done to treat it. We will come back to this.

Healthy and fatigued

How about people who are not sick? Can they be fatigued? Well it depends; among other things, on their job / gender / age and also their level of physical activity and even where they live (rural area or city). More than a third of employees declared in 2017 that they had experienced a burn out. Yet unemployed people are more fatigued. Is it fatigue or rather depression or anxiety? It is difficult to say and it is true that the barrier between these symptoms is sometimes tenuous. Women also report they are more fatigued on average than men. This reminds us of Scipio Dupleix who said at the beginning of the 17th century that “women, submerged by humours, softened by water, would be more fatigued than men”. Probably an ancestor of Eric Zemmour. What an idiot! I am obviously talking about Scipio! To evaluate the scientific level of this man, very likely a great ultracrepidarian, one can read what he wrote elsewhere, comparing walking and running, and attributing fatigue resulting from the latter to the sole fact that, contrary to walking, “the body is almost always in the air without being relieved and supported“.

More seriously, it should be noted that the greater fatigue of women is contrary to all the studies that show that they are more resistant to fatigability (acute fatigue), whether following local/single joint [18] or ultra-endurance [19] exercises. So why are women objectively less fatigued for a given physical task and more fatigued in daily life? Is it because of their superwomen’s schedule who do their second work day at home after finishing the first one at work? Probably..

The level of fatigue also depends on age. But not in the way we would expect. In one of our recent studies (so recent that it is not yet published) on the French population, we found that fatigue actually decreased with age until age 75, at which point it started to increase again. This goes against what one might intuitively think, since younger people are supposed to have more energy. Is this related to the fact that young people are, even more than older people, in chronic sleep deprivation because of new technologies and social networks? We don’t know, but it must be noted that sleep also deteriorates (for other reasons) at an advanced age, which would fit well with the results of our study.

What about the place of living? One would tend to believe that life in the countryside is more relaxing. Here again, findings indicate the contrary! How about the link between fatigue and level of physical activity? We talk in more detail about this further on in this article, but one should know that being active reduces fatigue. In summary, if you are a sedentary young woman looking for a job in the countryside, chances are you are very fatigued. But with all that, we still don’t know why we feel fatigued?

Which etiology?

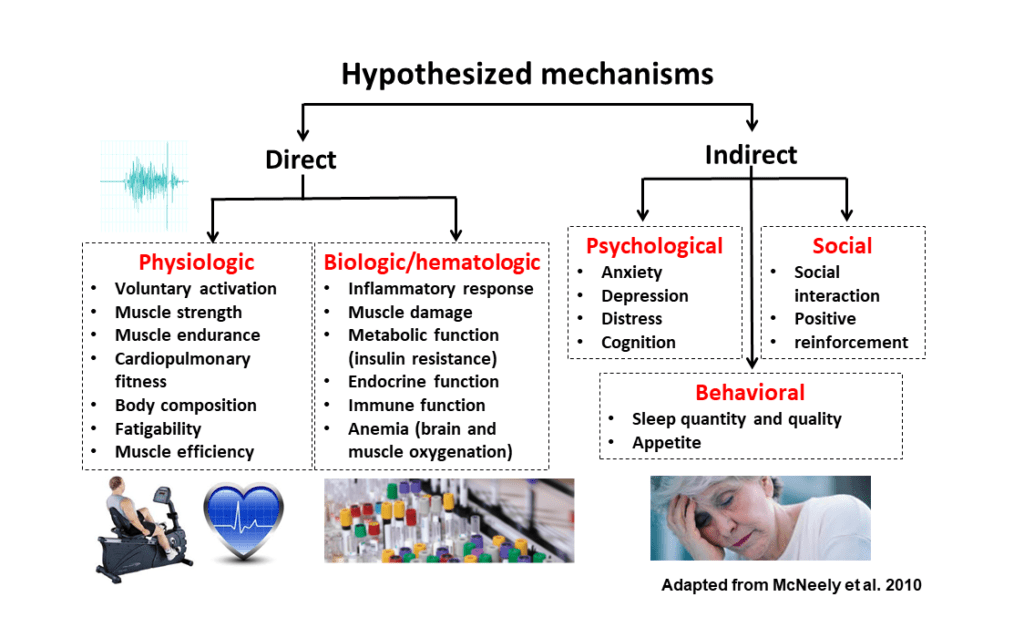

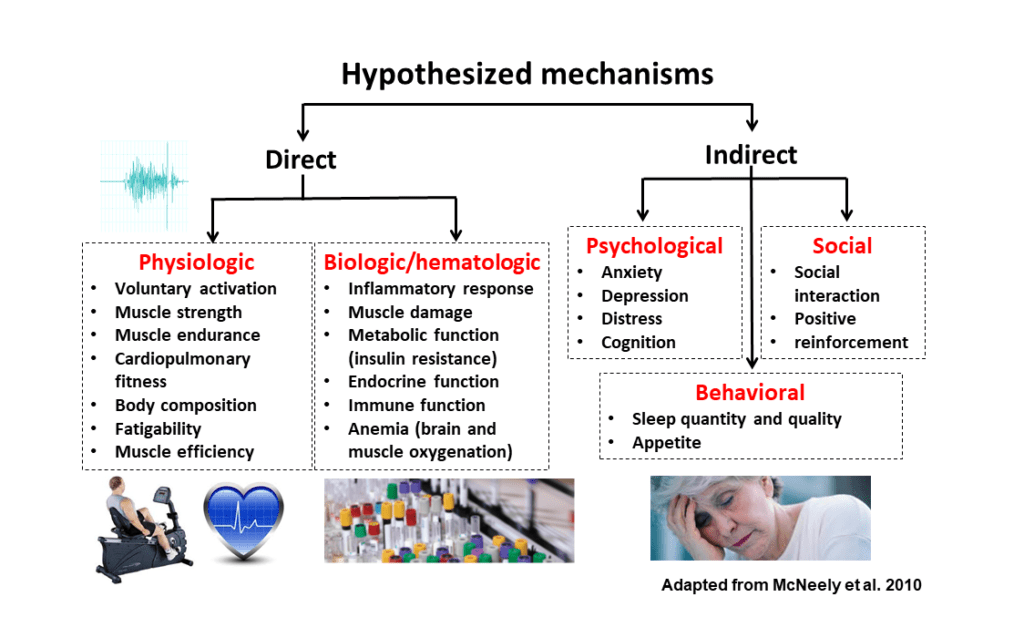

Let’s get back to chronically ill patients. Sometimes, fatigue can be easily traced back to the disease itself. For example, the level of disability in multiple sclerosis or the red blood cell count in certain cancers such as myelodysplastic syndromes. However, even when it is very pronounced, anemia does not necessarily explain fatigue completely [13]. In other words, the causes are usually multiple: two patients may have the same level of subjectively perceived fatigue for very different causes. The figure below shows the main mechanisms that have been identified to explain high levels of fatigue.

Obviously it would not be possible to discuss each of the potential causes in detail in this article. Especially since we have already discussed some of them, such as sleep disorders. It is worth noting that there is an overlap between certain psychological problems such as depression and fatigue: fatigue has even been presented as a potential predictor of a new depression in people who have already suffered from this problem in the past. However, fatigue and depression are not synonymous: for example, antidepressants do not often reduce fatigue. In this article, we will focus instead on the left side of the figure (physiology) and on the role of physical activity in fighting fatigue. We will ask the following question: can the deterioration of physical capacities (deconditioning), and more particularly a lower resistance to acute fatigue, explain, at least in part, chronic fatigue?

Part 2 will be published soon, stay tuned…

[1] In fact, some authors propose an even more complex taxonomy by differentiating between the state of fatigue (which depends on internal sensations and the psychological state of the moment) and the trait of fatigue, which is more latent, depending both on the resistance to objective fatigue and on what we have called above chronic fatigue assessed by questionnaires.